Art has always been a powerful reflection of human society, beliefs, and dreams. Beginning with the Renaissance, art evolved from a craft focused on religious themes to a sophisticated exploration of emotion, perspective, and individualism, shaping its role as a serious discipline. Here’s a quick journey through this evolution:

Renaissance (14th–17th Century): Rebirth of Classical Ideals

The Renaissance, meaning “rebirth,” was a period of renewed interest in the classical philosophies of Ancient Greece and Rome. This shift was fueled by political stability, economic prosperity in Europe, and the rise of powerful city-states like Florence. Wealthy patrons, especially the Medici family in Italy, funded art to display status and foster intellectual growth.

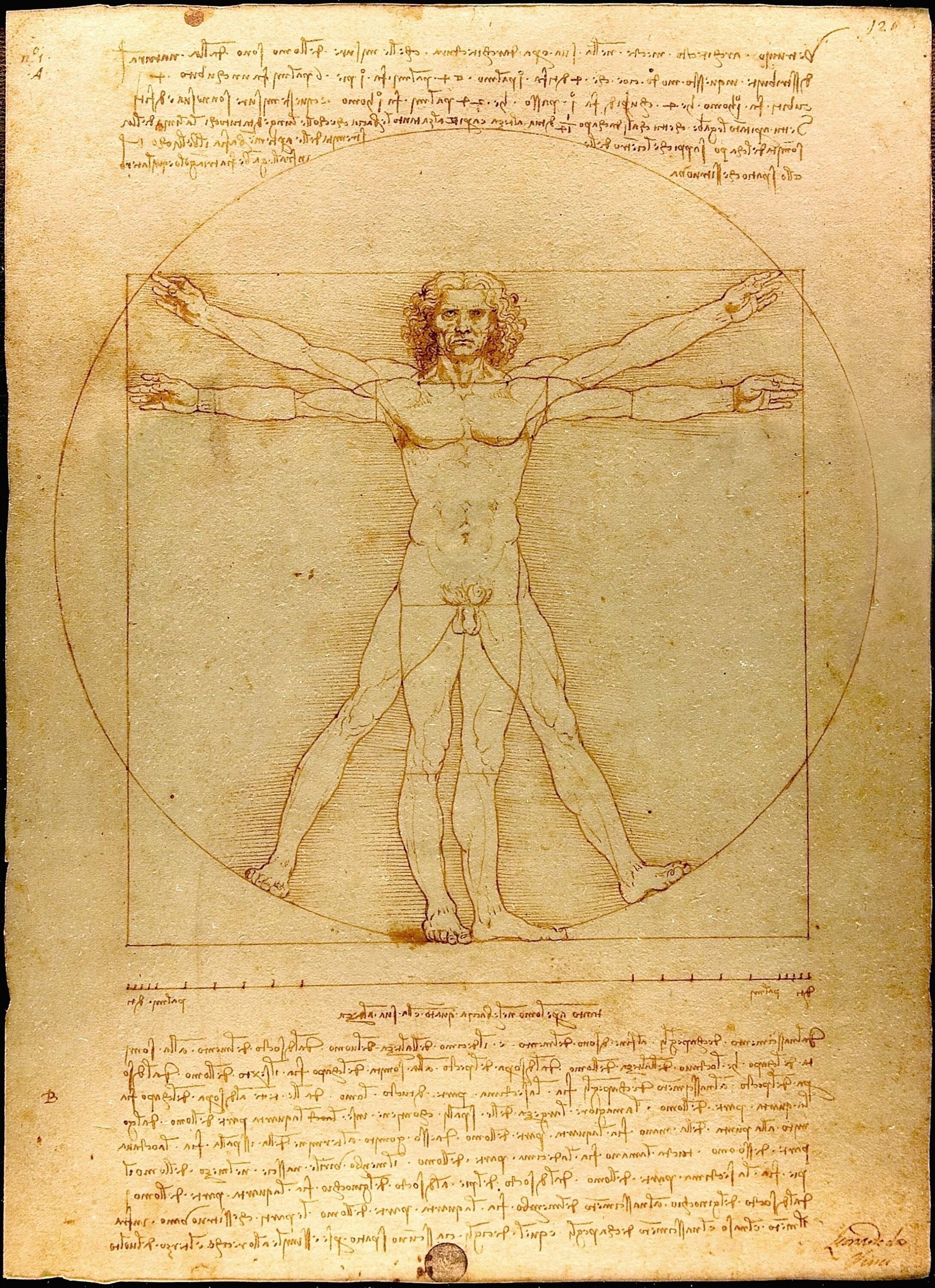

Art moved away from the stiff religious iconography of the medieval period, embracing humanism—a philosophy that emphasized human potential and achievement. Artists studied anatomy, perspective, and nature to capture the world realistically, as seen in Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man and Michelangelo’s David.

Renaissance artists challenged medieval art’s spiritual focus, instead exploring science, beauty, and secular themes. They valued harmony, proportion, and balance, seeing art as an intellectual pursuit, which raised the artist’s social status.

Baroque (1600–1750): Drama and Power

Following the Reformation, the Catholic Church responded with the Counter-Reformation, using Baroque art to convey religious fervor and drama. Absolute monarchies (like France under Louis XIV) used the style to reflect power, control, and grandeur.

Baroque art used intense contrasts, dynamic compositions, and emotional intensity to captivate viewers. Artists like Caravaggio emphasized realistic, dramatic scenes with strong light and shadow, which brought sacred and secular themes to life.

Baroque was a response to both Renaissance ideals and Protestant criticism, turning art into an emotional, visually striking experience to reaffirm the power of the Church and state. It emphasized spectacle and drama, contrasting with the calm rationalism of the Renaissance.

Neoclassicism (18th Century): Rational Order and Heroism

The Enlightenment, which emphasized reason and science, transformed how people saw art and society. Political revolutions in America and France called for democracy and equality, inspiring art that promoted civic duty and sacrifice.

Neoclassicism looked back to ancient Rome and Greece, embodying virtues like courage and patriotism. Artists like Jacques-Louis David depicted historical and mythological scenes with clarity, symmetry, and stoic emotion, as seen in The Oath of the Horatii.

Neoclassicism rejected the ornate, dramatic flair of Baroque, instead favoring rationality, structure, and moral themes. It reflected a desire to restore order and heroism, echoing the political calls for social reform and rational governance.

Romanticism (Late 18th–Mid 19th Century): Emotion and Nature

The Industrial Revolution and the rapid growth of cities made people yearn for nature and individuality. In an era marked by factory labor and social upheaval, Romanticism sought to reconnect with the natural world and personal emotions.

Romantic artists, like J.M.W. Turner and Caspar David Friedrich, focused on dramatic landscapes, exoticism, and human vulnerability. They conveyed awe, passion, and sometimes terror, portraying nature as a powerful force beyond human control.

Romanticism emerged as a counter to Neoclassicism’s strict order, offering a more subjective, emotionally intense view. It reacted against the rationality of the Enlightenment, embracing imagination and the sublime to express a deep connection with nature and the individual.

Realism (Mid-19th Century): Truth to Life

Industrialization caused major social shifts, with crowded cities and poor working conditions. The social inequality of this time inspired artists to focus on ordinary people and daily life.

Realist artists like Gustave Courbet and Jean-François Millet depicted peasants, workers, and urban life without idealization. Realism emphasized authenticity, portraying people’s struggles and labor with honesty.

Realism rejected Romanticism’s escapism and idealization. Instead, it focused on societal issues, aiming to provoke awareness and empathy for the working class. Realist art pushed boundaries by confronting viewers with unembellished realities.

Impressionism (Late 19th Century): Capturing Fleeting Moments

By this time, Paris was modernizing, with new boulevards, parks, and cafes that encouraged social interaction. Technological advancements, like portable paints and new pigments, allowed artists to paint outdoors.

Impressionists, such as Claude Monet and Edgar Degas, painted en plein air (outdoors) to capture light and movement. They used quick brushstrokes to portray fleeting moments, often focusing on everyday scenes and landscapes.

Impressionism broke from Realism’s focus on accuracy, embracing spontaneity and subjective experience. This was seen as radical, as Impressionists prioritized the artist’s perception of a scene over precise detail. They faced criticism but ultimately reshaped public perception of what art could be.

Modernism (Late 19th–Mid 20th Century): Breaking Boundaries

As Europe moved into the 20th century, rapid urbanization, world wars, and scientific progress challenged traditional values. Artists questioned old conventions and sought new ways to express the anxieties and complexities of modern life.

Modernist artists like Picasso (Cubism), Matisse (Fauvism), and Kandinsky (Expressionism) experimented with form, color, and abstraction. They challenged traditional perspective, using geometric shapes, bright colors, and symbolic imagery.

Modernism was a reaction against the restrictive norms of art and society. It sought to express inner emotions, abstraction, and fragmentation, reflecting the disillusionment of a changing world.

Surrealism (Early–Mid 20th Century): The Subconscious Explored

Influenced by Freud’s theories on dreams and the subconscious, Surrealism emerged as a response to the horrors of World War I. The movement reflected a desire to escape reality and explore the mind’s depths.

Surrealist artists like Salvador Dalí and René Magritte created fantastical, dreamlike scenes that defied logic. They aimed to unlock subconscious thoughts, merging the real and the imagined in a surreal blend.

Surrealism was a radical rejection of rationality, celebrating the irrational and bizarre. It sought to liberate the mind, tapping into the unconscious to reflect the chaos and trauma of the post-war period.

Abstract Expressionism (Mid 20th Century): Pure Expression

In the wake of World War II, American artists sought freedom from European traditions. They explored self-expression as a response to existential questions in an era shaped by conflict.

Abstract Expressionists like Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko used non-representational techniques to convey emotion directly through color, form, and spontaneous movement. Pollock’s drip technique embodied freedom, while Rothko’s color fields offered meditative spaces.

This movement rejected structured composition and symbolism, favoring raw, unfiltered expression. Abstract Expressionism was a reaction against order and formality, mirroring post-war existential questions.

Contemporary Art (Late 20th Century–Present): Diversity and Innovation

With globalization, digital technology, and identity politics, contemporary art encompasses diverse media and perspectives. It reflects complex, multicultural, and interconnected issues.

Contemporary art is highly varied, with movements like Pop Art, Conceptual Art, and Digital Art exploring everything from consumer culture (Warhol) to political critique. Artists experiment with materials, installations, and interactive experiences.

Contemporary art resists categorization, reflecting the diversity and complexity of modern life. It often challenges traditional concepts of art, incorporating social critique and innovation that connects deeply with audiences today.

Conclusion

So basically, art has evolved from the strict realism of the Renaissance to today’s vast, eclectic landscape where nearly anything goes.

Each era challenged or expanded the boundaries set by the one before, pushing art beyond mere representation to embrace personal expression, social critique, and even humor.

Here’s a quick breakdown of this historial art journey:

- Renaissance (1300-1600) – Set the standard for realism, precise anatomy, and idealized beauty.

- Baroque (1600-1750) – Pushed drama and emotion with high contrast and theatrical compositions.

- Neoclassicism (1700) – Embraced order and heroism, drawing on ancient models for clarity.

- Romanticism (1750-1850) – Reacted by valuing emotion, imagination, and awe of nature.

- Realism (1850) – Turned to everyday life, showing people and places with honesty, no idealism.

- Impressionism (1850-1900) – Focused on light, color, and momentary impressions, moving away from clear details.

- Modernism (1850-1950) – Broke away from realism entirely, exploring abstract forms, perspectives, and social commentary.

- Surrealism and Abstract Expressionism (1900-1950) – Dived deep into the subconscious and pure emotion, moving further from literal representation.

- Contemporary Art (1950–now) – Welcomes diverse media, messages, and methods, with styles ranging from realism to conceptual and digital.

Today, art has become as much about ideas and experience as about visual form. You’ll find realistic portraits, abstract experiments, digital works, and installations coexisting, each an avenue for artists to explore ideas, social issues, or even cultural critique. It’s no longer about “how well can I represent reality?” but “what can I say, show, or question with this work?”